It should have been clear to those who hired Martin as acting chair of the sociology department at the University of Saskatchewan that he was neither an experienced administrator nor particularly interested in the practice of sociology as a narrow academic discipline. Martin’s career after the Supreme Court decision had followed a traditional trajectory. He had taught at four different colleges and universities, completing a Ph.D. in sociology at the University of Wisconsin along the way. He’d moved through the ranks from instructor to associate professor until he got the job at the Regina campus. It should have been clear to those who hired Martin as acting chair of the sociology department at the University of Saskatchewan that he was neither an experienced administrator nor particularly interested in the practice of sociology as a narrow academic discipline. Martin’s career after the Supreme Court decision had followed a traditional trajectory. He had taught at four different colleges and universities, completing a Ph.D. in sociology at the University of Wisconsin along the way. He’d moved through the ranks from instructor to associate professor until he got the job at the Regina campus.

In Martin’s previous job at Antioch College in Ohio, and with the encouragement of his department, his research had consisted of working in the black community as an organizer in the War on Poverty (a government initiative), helping poor blacks claim their rights to health care, education and food. He loved the work but nonetheless felt discouraged. In the summer of 1966 he wrote to a Quaker friend, “The experience of organizing poor Negroes in Dayton...has become the highlight of my life so far....In spite of all the successes, I am pessimistic and see a dark future. I hope I shall be proven wrong.” Elsewhere in his letter, he noted, sadly, that Martin Luther King’s “symbolic power” was waning and a more militant black leadership was taking its place.

From the moment he arrived in Regina, he was at odds with the faculty and administration. He informed the students in the sociology department that henceforth they would participate in all decisions of the department, including hiring and curriculum. A front page article in the student paper, The Carillon, quoted Martin saying, “We can’t run...universities the way we ran them when we were students....Consumer participation is the key to future democracy.” And he added, “When faculty stop learning, [they] ought to get fired.” From the moment he arrived in Regina, he was at odds with the faculty and administration. He informed the students in the sociology department that henceforth they would participate in all decisions of the department, including hiring and curriculum. A front page article in the student paper, The Carillon, quoted Martin saying, “We can’t run...universities the way we ran them when we were students....Consumer participation is the key to future democracy.” And he added, “When faculty stop learning, [they] ought to get fired.”

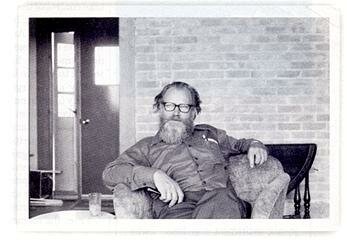

His colleagues were incensed. In theory they subscribed to the notion of participatory democracy. But their radical new German-American chair, who with his bushy beard was now looking more and more like an Old Testament prophet, was proposing to give students power before they’d even asked for it. Faculty had only recently acquired a measure of power themselves. Nor did they think much of Martin’s research activities; he was doing social work — helping aboriginals and low-income single mothers to organize.

Bravely or naively, Martin then suggested to his colleagues, many of whom could be described as armchair Marxists, that the sociology department be run on good Marxist principles (if pressed, Martin would have described himself as a democratic socialist). He proposed that he and the other members of the department pool their salaries and then divide the money according to need. Those with children or elderly parents to support, for instance, might need more than those without. Martin was serious; his colleagues were appalled.

Martin himself now lived alone. He and Becky had divorced in 1961. Their different values had come to affect every aspect of their lives. Martin’s belief in simplicity included owning no property. Becky wanted a house. Martin wanted the boys to attend public schools; Becky enrolled them in private schools.

His status as a bachelor changed the first fall in Regina. Martin met Joy Rowe, a high school art teacher, at a public lecture sponsored by the University. At the end of the evening, they went for coffee. They met again not long after at a conference on the north and community development. Despite their age difference — Joy was twenty-four; Martin was fifty — they shared common values. Both were pacifists and believed in empowering people.

They married in April of 1968 in a modest Quaker ceremony, followed a day later by a civil ceremony. They moved to a rental property on a hill overlooking the town of Lumsden in the Qu’Appelle Valley, not far from from Regina. Joy and Martin came to love the place, with its view below of trucks and railway cars hauling grain to and from the elevators. So when their landlord tried to evict them a few months later, they bought the house for $5,000, despite Martin’s reservations about owning property. Martin had grown a bushy beard and looked like an Old Testament prophet. Joy wore her hair and her skirts long. Puzzled neighbours referred to them as “those hippies.”

They furnished the home with what they affectionately called “the family burden,” heavy and expensive German oak and cherry pieces that Else had brought with her to America. (That’s all she was allowed to bring.) Living in Lumsden energized Martin. His interest in agriculture was revived; he met with farmers and others to promote chemical-free agricultural practices, something of a heresy in the late sixties and early seventies. Later he, Joy and three others financed and ran a small dairy on a homestead near Yorkton; they supplied the neighbouring area with goat’s milk, cheese and meat.

Martin’s Room, continued >

|